1950s and ’60s: Point San Pedro up for grabs

Development (and motorcycles) threatened to destroy China Camp village and more

The following is the final chapter in our three-part series on the history of Point San Pedro, covering major events from the McNear family ownership in the 1860s, to the creation of China Camp State Park in the 1970s. In this final segment, author and FOCC volunteer Kevin Smead sheds light on the last gasp for rampant development in the 1960s, and how the land was finally protected as parkland.

It was the 1950s, and E.B. McNear’s health was failing. Income from grazing leases in the Back Ranch Meadows area and other parts of the McNear ranch were declining. So when the Stegge Development Company made an offer in 1955 (the year before E.B.’s death) to buy much of the McNear land, the family said yes.

Stegge began developing the southern part of the property, in the San Rafael neighborhood now known as Glenwood. In 1956, Stegge sold most of its property (save for the McNear’s “Palm Beach” resort-style area on the southwest end of the property). The buyer was Latipac, a Hawaii-based real estate development firm headed by Chinn Ho, a charismatic Chinese-American. (Some newspaper accounts have confused him with actor Kam Fong, who played the character Chin Ho on the original 1960s version of “Hawaii 5-0.”)

Razing the village in the name of development

Latipac and others proposed a massive development first called “Riviera Marin” and later “Marin Bay.” The project envisioned “private multi-acre estates” in the hills on the north end of the parcel and dense residential and commercial development along the San Pablo Bay shoreline. In the mix was a plan to raze China Camp Village, replacing it with “China Cove,” an exclusive development with a private yacht club, boutiques, restaurants, a “boatel” for visiting yachtsmen, a hotel on what is now Village Point, and glass-enclosed funiculars carrying guests to a resort tucked in the hills. In addition, there would be “handsome residential areas in the nearby hills and valleys.”

Describing the area as “land which has always been looking for people,” project publicists suggested that 20,000 residents would soon be living in Marin Bay. “Wooded single and apartment house sites with waterfront views,” plus berths for some 3,000 pleasure boats, would be created. “Homesites, complete with stables,” would be perched in the northern hills, adjacent to a 400-acre “natural preserve.”

On Rat Rock Island, developers would perch “an international restaurant, with access by a swinging bamboo bridge.” Also on tap: five school sites and three shopping centers. But the times, as the Dylan song extols, “they were a-changin.”

Anti-development sentiment takes hold in Marin

By the mid-1960s, there was a growing environmental movement in Marin County that sought to put the brakes on rampant development of its beautiful hills, valleys, coastline, and wetlands. Already, there was pressure to stop a massive project, called Marincello, in the Marin Headlands, and similar efforts began to take shape to curb the huge development proposed for the San Pedro Peninsula.

When water quality issues slowed the build-out of the area known as Peacock Gap, East San Rafael environmentalists organized, using the pause to raise funds and awareness. Their first victory came in 1970, when the Palm Beach resort portion of the property was purchased by the county and protected as McNear’s Beach County Park.

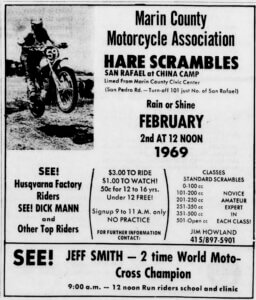

That still left a significant undeveloped chunk of the McNear’s former holdings, including the village area. With development stalled, raucous and sketchy activities were the norm, and the land took on a seedy air. Young people could hang out and have bonfires beyond the gaze of adult eyes. Destructive dirt-bike riding in the hills, and even motorcycle races sanctioned by the Marin County Motorcycle Association, ripped up the earth. From 1967 to 1970, the Renaissance Pleasure Faire brought 10,000 visitors daily to China Camp during late summer and early fall weekends. And, in 1975, there was a notorious murder case linked to the area around Back Ranch Meadows.

State park designation and protection at last

But the land’s historical and natural features remained undeniably important and worthy of protection. In 1976, the California State Parks Foundation purchased 1,476 acres from Chinn Ho. A year later, the state legislature approved funding for the creation of a new park on the peninsula, and the land was transferred to the state for $2.13 million. In addition, Chinn Ho donated the 36 acres containing China Camp Village to be saved as a historic site, declaring “[t]he historic value of China Camp underlines the significant place in California and Bay Area history held by Americans of Chinese origin.” On January 13, 1978, China Camp State Park was officially designated.

While the creation of county and state parks technically protected the acreage, there were still challenges and management decisions ahead, including traffic impacts through adjacent neighborhoods and camping restrictions. Motorcyclists unsuccessfully sought continued access. A network of official trails were blazed by the state, some following tracks that had been made by dirt bikers. Numerous unofficial “social” trails were carved out by bikers and hikers over the years—a dangerous and destructive practice which continues to this day.

In 2008, state budget cuts threatened the closure of most state parks, including China Camp. The park weathered that storm, but in 2011 it appeared likely that due to ongoing budget woes, China Camp would be shuttered. However, the community, banded together by newly formed Friends of China Camp, stepped in to keep the park open. In 2012, legislation was enacted that would allow the state to enter into operating agreements with local non-profits, allowing organizations like FOCC to assume management of parks that were threatened with closure. Friends of China Camp took over park operations, relying almost exclusively on volunteers, and continues to this day to manage China Camp State Park.

But it’s been said that the only constant is change. What will happen to this land in future years? Only time will tell. But we all–individually and collectively–have the power to be a part of that change.

—by Kevin Smead/FOCC volunteer