The McNears: Dreams, schemes, and ambition

How a family from Maine put its stamp on Point San Pedro

Home to indigenous Miwok. A poorhouse. Railway lines. A coaling station. Naval dry docks and an academy. Ferries for trains. A brewery. The Richmond – San Rafael bridge terminus. A military range. A 1,000-bed veterans hospital. A tidelands dump for San Francisco garbage. Thousands of homes. Marinas. A “boatel.” Shopping centers. A swinging bamboo bridge to a restaurant on Rat Rock Island.

These ideas and more were serious proposals for the Point San Pedro peninsula and the land that is now protected as China Camp State Park. Today’s landscape wasn’t inevitable–it’s a product of the choices we have made over time.

The following article, the first in a three-part series, sheds light on the McNears. They were one of the North Bay’s most influential families following the gold rush, and their activities and choices–and those of others–impacted the region’s landscape and shaped its future.

The McNears: Brothers with big dreams burst onto the scene

When we look at a place like China Camp State Park, with its serene salt marshes, its soaring hills, and its expansive oak and bay woodlands bounded by grasslands, it’s easy to think that what we see now is what always has been. Of course, history informs us otherwise. For centuries, the indigenous Miwok tribes managed the land with regular fires. Near their villages, enormous shell mounds rose up, the discards of shellfish, a major food source for the Miwok.

In the early 1800s, holders of Mexican land grants and their heirs claimed ownership and established ranches on Point San Pedro. Dairy cattle roamed the land. Following the gold rush, Chinese immigrants settled along the shoreline of San Pablo Bay, raising their families in shrimp-fishing villages like the one at China Camp, the remnants of which still stand today.

Some of the peninsula’s land owners dreamed big, and none more so than members of the McNear family. John A. McNear, a sailor from Maine with a knack for business, joined by his entrepreneurial brother George W., came to Petaluma soon after the gold rush. Both succeeded wildly: John made his name in real estate, shipping, and manufacturing; George became the “grain king” of California.

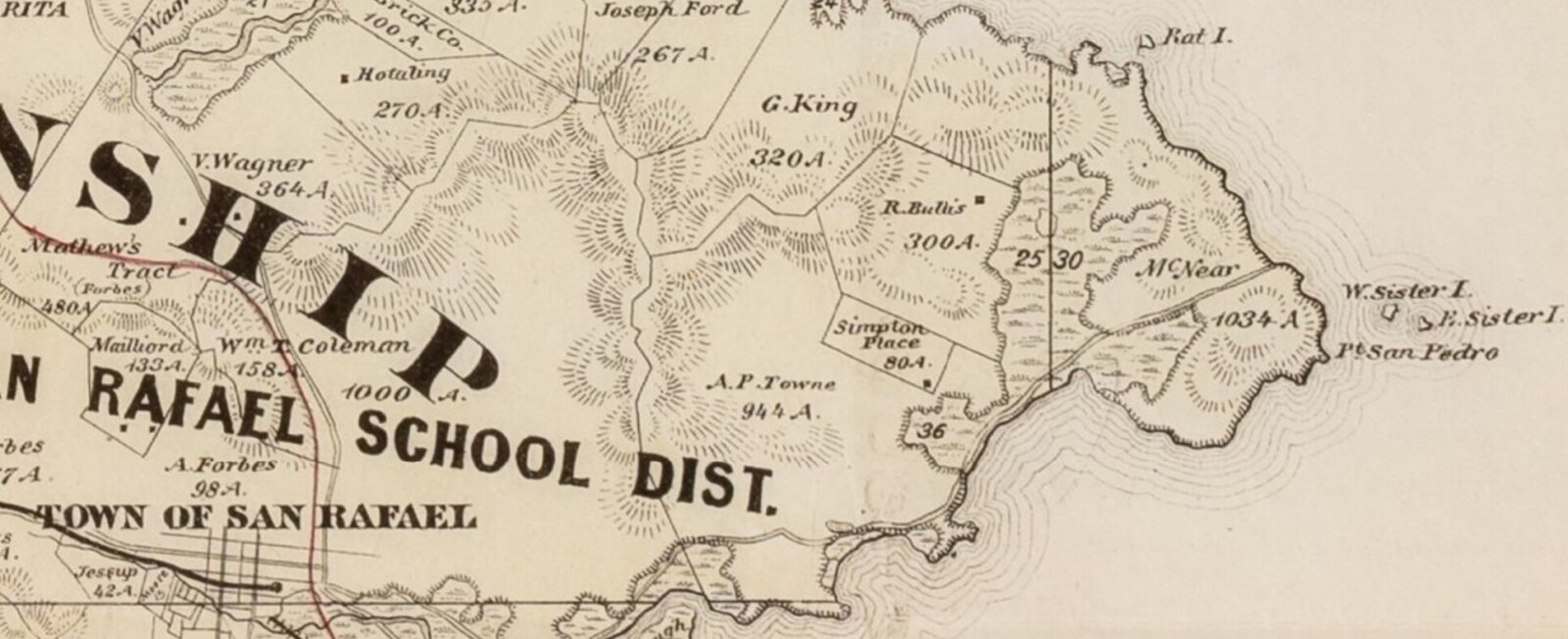

In 1868, the brothers acquired 700 acres of shoreline property on Point San Pedro. They intended to build a wharf and other shipping facilities to complement those that they owned in Petaluma. In 1889, John bought out George’s interest; over the next 15 years he increased his landholdings on the peninsula to some 2,500 acres, including the land that would one day become China Camp State Park. As his landholdings expanded, so did John (or “J.A.”) McNear’s dreams for them.

Both McNear brothers resided in Petaluma for the rest of their lives, leaving much of the day-to-day ranch operations in the hands of hired superintendents. The McNears earned some income from dairying and by leasing a portion of their lands for cattle grazing. The brothers also collected rent from the Chinese shrimpers who had set up several shrimping villages along the shoreline shortly before the McNears took over ownership.

But J.A. McNear had bigger plans for the land. To fulfill his broader ambitions of creating profitable recreational and business opportunities on the McNear acreage, transportation had to be improved. In 1880, the McNear brothers offered the county 60 acres of their land for a poorhouse, provided the county built a road to it. The county didn’t bite, and the facility was eventually built in Lucas Valley. So J.A. subsidized the building of a road from San Rafael to McNear’s Point and onward. This provided access to the growing resort (on land that’s now a county park called McNear’s Beach). It’s here that J.A. built his wife a summer home. But road-building alone wasn’t sufficient to fulfill his dreams.

Dreams of a West Coast Coney Island and electric streetcars

In J.A.’s mind, the linchpin for realizing the potential of the point was a railroad line. This could bring day-tripping passengers to his resort (“a Pacific Coast Coney Island” was contemplated). It could also carry potential homebuyers to the land. J.A. had already invested in a successful rail line between Petaluma and Santa Rosa. His vision was to extend line to his land on Point San Pedro and then on to San Rafael.

In the late 1800s, the electric streetcar drove suburbanization across America, and it was a hot topic in San Rafael. Competing interests sought a street railway franchise. A group supporting McNear and his vision was so confident of success that in 1906, it began grading a rail route through McNear‘s lands. The route followed what is today Peacock Drive. It continued past the McNear’s family dairy buildings, then headed just west of what are now the 8th and 9th holes at the Peacock Gap Golf Course.

Grading continued up through the gap in the hills into what is now the corporation yard and ranger station for China Camp State Park. (The ranger station sits on the site of the Peacock family residence.) Finally, it was to head northwest along the shoreline toward Santa Venetia. Railroad spurs would serve McNear’s Point, the site of a quarry, a brickyard (operated since 1900 by the McNear family), and an increasingly popular resort.

But timing can be everything. The great 1906 earthquake put plans for the railway on hold. Automobiles became king, and rail plans were shelved. Even the county road’s extension to Santa Venetia, for which the McNears granted a right of way through their lands and offered assistance in its construction, took longer than almost everyone expected. The transition from a farm road to a paved North San Pedro Road wasn’t completed until 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression.

J.A. McNear and his sons—George P., Dr. John A., and most significantly Erskine B.—persevered, trying to keep the railroad dream alive. In addition to an existing passenger ferry at Point San Pedro, J.A. championed ferries that would carry train cars from the East Bay to the peninsula. He envisioned that the trains would continue northward, following rails to Petaluma and beyond.

But the future kept overtaking his dreams. By the 1920s, it was clear that a car-carrying bridge would one day cross the bay from the East Bay to Marin. E.B. fought to have its Marin terminus located at Point San Pedro. Unfortunately for the McNears, the ferry and bridge plans both lost out to interests favoring Point San Quentin.

But the McNears continued to have vision and ambition, with plans that changed with the times. And even though their dreams didn’t all come to fruition, the family still put its mark on indelibly on the land.

——————

In our Summer 2024 newsletter, we’ll look at the next phase of history impacting Point San Pedro, including planned developments spurred by military expansion and wartime. We’ll also explore a variety of commercial schemes and residential development proposals that would have radically altered the landscape. Finally, we’ll take a closer look at the twisting tale of how most of what had been the McNear ranch for nearly a century ended up becoming state parkland.—Kevin Smead/FOCC volunteer