In-depth report sheds light on China Camp’s history

An excerpt from the park’s “Cultural Landscape Reports” make for a fascinating read.

As part of its mission to preserve and protect the history of China Camp, and as managers of a parcel protected by the California State Park System, Friends of China Camp created Cultural Landscape Reports (CLRs) of China Camp State Park. To do that, a comprehensive review of the park’s historic landscapes was needed to help understand their significance, and preserve, protect, and enhance them for the future. This written review helps us record and manage key historic sites, providing a “wholistic analysis of all the resource types therein.”

In FOCC’s efforts to shed light on our work, and because it makes for some pretty interesting and enlightening reading about the park, we are sharing an excerpt from the report here. The excerpt focuses on the key facts and features in China Camp’s history. We hope you enjoy reading it. And a huge shout-out to FOCC Board Member John Muir for his extensive work on this fascinating report.

Excerpt: China Camp Cultural Landscape Report

China Camp State Park is located in San Rafael, Marin County, California, on the western shore of San Pablo Bay. The 1,514-acre park was established in 1976 and includes extensive areas of shoreline and hiking trails in addition to the historic China Camp village.

Within this document, the terms China Camp, China Camp village, and China Camp settlement are synonymous, and refer to the cluster of structures and associated landscape features in the cove south of Rat Rock, north of McNear’s Beach County Park, and east of North San Pedro Road. The terms China Camp State Park, China Camp park, or the park refer to the larger state park unit of which the village is the historic core.

Within this document, the terms China Camp, China Camp village, and China Camp settlement are synonymous, and refer to the cluster of structures and associated landscape features in the cove south of Rat Rock, north of McNear’s Beach County Park, and east of North San Pedro Road. The terms China Camp State Park, China Camp park, or the park refer to the larger state park unit of which the village is the historic core.

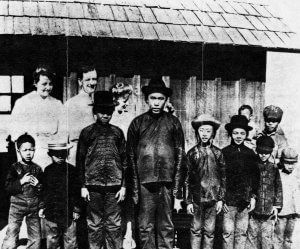

Settlement at China Camp is believed to have begun in the late 1860s as Chinese immigrants from the areas around the Pearl River delta, who had been employed in the construction of the transcontinental railroad, began to seek other means of livelihood. Employing traditional bag nets and small craft, they harvested shrimp from shallow waters along the shores of San Francisco Bay, and sought out nearby parcels of land where the catch could be quickly landed and spread out to dry. One such settlement was China Camp, which first appears in the historic record in maps from the 1870s, and grew rapidly in the subsequent decade.

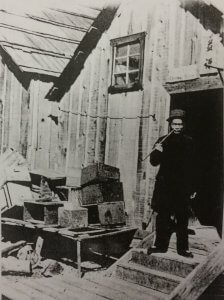

By the late 1880s, the settlement consisted of some 400 Chinese, mostly men, and approximately thirty buildings and sheds, densely packed in loose rows parallel to the shoreline, with a number of wharves extending into the water and sampans or junks alongside or moored nearby, and drying platforms interspersed along the flats behind the beach or created by clearing and raking the slopes of the adjacent hillsides.

The busy nature of the enterprise was not unnoticed by the white citizens nearby, especially by fishermen and others who saw the Chinese as unwelcome competition. Circumstances of Chinese migration had created a situation where they lived as outsiders within the larger society, and nativist feeling rose with economic competition and hard times to a crescendo with the enacting of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This, combined with increasing pollution/sedimentation of the bay and regulatory pressure by the Fish and Game Commission and other state and local authorities, led to a gradual decline in the size of the settlement that only amplified with the use of motorized junks and the implementation of a ban in 1911 on the type of set bag nets they used.

Census data indicates that all of the Chinese fishing settlements around San Pedro Point had 347 occupants in 1880, but had declined to a mere 79 in 1900.

By the 1920s, the shrimp fishing settlement had largely evolved into a camp that catered to local sport fisherman, supplying motorized skiffs and rowboats to visiting locals who came to use rod, hook and line to fish for Striped bass and White sturgeon that were still plentiful in the nearby waters of San Pablo Bay. With fewer residents, and a shift from large scale shrimp processing to a small supplemental shrimp trawling operation, the settlement became less of a village and more of a family operation. Shrimp camp structures evolved into or were replaced by structures serving a clientele of daytime visitors.

After WWII increasing pollution and shoreline landfill further degraded the San Francisco Bay ecosystem as the fishing settlement lingered on. A flurry of excitement and activity intervened when the “exotic” location was used for a time in the 1950s as a set for the Hollywood movie “Blood Alley.” The threat of further development in the area brought a movement to save the natural shoreline and historic site, which culminated in the acquisition of the area by the state and the establishment of China Camp State Park as a unit of the state park system in 1976. A master plan was created for the park in 1978 and a period of stabilization, repair and rebuilding of the remaining historic structures resulted in the establishment of an interpretive program and preservation of the historic landscape that we have today.

China Camp is therefore considered significant to the history of California in the areas of Commerce, Industry, Maritime History, and Asian Ethnic Heritage, and the context of The Chinese in California: Fishing, from Early Settlement to Integration, 1869-1976. China Camp was registered as a California Historical Landmark on December 7, 1978. and entered onto the National Register of Historic Places on April 2, 1979.