The Quan Family: China Camp’s dynasty

How one family made an indelible impact on the land that become China Camp State Park

In the late 1880s, the bay-front village that had come to be known as China Camp boomed, with nearly 500 people living in the shrimp-fishing village in the shadow of San Pablo Mountain. All that changed in the early 1900s, when a series of racist laws and regulations were enacted. These laws, including a ban on the bag nets used by Chinese fishermen and an embargo on the international export of shrimp, put a stranglehold on China Camp’s fishermen. It became virtually impossible for Chinese shrimpers to make a living using traditional methods.

While many families packed up and left China Camp, one clan stayed: the Quans. This important family made an indelible impact on how China Camp was settled, how it changed in the face of systemic racism, and how it ultimately became a California State Park. The story begins with the family’s patriarch, Quan Hung Quock, who had left China’s Pearl River Delta in the Guangdong Province in the 1880s, and ended up in San Francisco.

But by the turn of the century, Quan, like other Chinese immigrants, faced rampant racial persecution in the city. He fled north from San Francisco to a burgeoning shrimp-fishing village–the area now known as China Camp–in Marin County. The surrounding waters were filled with native (and edible) grass shrimp, which village fishermen caught using traditional Chinese bag nets and traditional fishing junks. Quan opened a general store for the burgeoning village, and started to raise his family.

Quan Brothers shrimp fishing takes to the water

But Quan Hung Quock and the other China Camp villagers still couldn’t dodge discrimination. By the early 1900s, fishing laws and restrictions clamped down, targeting the traditional methods used by Chinese shrimp fishermen. Regulations closed the bay to shrimp fishing during peak months. Other California laws forbid the sale of dried shrimp to international markets, like China.

Villagers adapted as best they could, but a 1911 prohibition on the fishermen’s traditional bag nets all but wiped out China Camp and other villages. Without nets, the fishermen couldn’t catch shrimp, and a way of life began to fade away.

Legal nets and new ventures

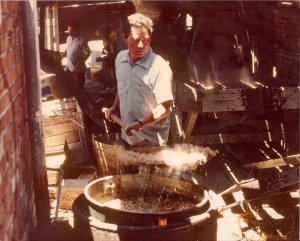

The Quan family hung in there, and in 1914, good fortune arrived on the bay in the form of a new kind of fishing net, called a trawl. The two eldest Quan sons, Henry and George, hooked up a trawl net behind a power boat and cruised through the water. Soon, they were catching, processing, and cooking thousands of pounds of shrimp a day—all without violating discriminatory laws.

The Quan family began to grow. In 1924, son Henry Quan wanted to marry a Caucasian woman named Grace, whom he’d met at a party. Since California law forbade unions between Caucasians and Chinese, Henry and Grace had to travel to Reno, Nevada, to wed.

Soon, locals began to discover the village’s quiet cove and beach, and the Quans took notice. New ventures were added to supplement shrimp fishing, and the whole family pitched in. After school, the Quans and their cousins helped out in the China Camp Cafe (still open on weekends to this day). Customers gobbled up 15-cent hot dogs and fresh shrimp cocktail. In addition to the cafe, a fleet of rental boats bobbed offshore.

Grace Quan stood out as the unforgettable matriarch. She even managed a deal to have her family and friends work as extras in the 1955 Lauren Bacall/John Wayne adventure drama, Blood Alley, which was filmed largely at the village.

Shrimp fishing dies, but Frank Quan stays

According to Frank Quan, diversion of river waters in the 1960s for the California State Water Project dealt the final blow to commercial shrimp fishing at China Camp. With freshwater sources diverted to a thirsty Southern California, the bay grew saltier—too salty for grass shrimp. Pollution also took a toll.

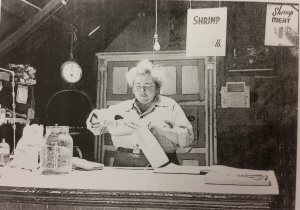

Courtesy Frank Quan Collection

“When we were kids, there was just so much fish,” Quan said in the 2011 Huffington Post piece. “Now it’s almost like a desert out there. We just watched it slowly die in front of us.”

While others packed up and left, Frank stayed on, living in a small cabin in the village and running the cafe with his cousin Georgette. Occasionally he would take out his boat and drag the water in hopes of catching a few shrimp. Sometimes he did, and sometimes not. Frank Quan passed away in 2016, the last resident shrimper at China Camp.

Though no Quans live at China Camp now, their legacy lives on. Frank, brother Milton (who is still alive), and others were instrumental in perhaps were instrumental in staving off development on 1,500 acres of San Pedro Ridge, including the historic fishing camp, by supporting the 1977 establishment of China Camp State Park.

More reading:

“Shrimp, subs, and superstars: the colorful life of China Camp’s Milton Quan,” Friends of China Camp Newsletter, Summer 2020

“Frank Quan, Lone Resident Of China Camp State Park, Faces Eviction,”Huffington Post article, August 24, 2011

“China Camp State Park: Where past and present live side by side,” KALW Public Media audio interview with Frank Quan and FOCC board member John Muir, August 23, 2016

Frank Quan obituary, Marin Independent Journal, August 19, 2016

“Frank Quan, Last Fisherman In China Camp, Dies,” KPIX 5 video of Frank Quan at China Camp Village, August 18, 2016