An untold love story

A volunteer recalls the incredible story of his grandmother, Tye Leung Schulze

Every family has its stories. Here, Ted Schulze, a Friends of China Camp volunteer, shares the story of his grandmother, Tye Leung Schulze. Tye spent her childhood in San Francisco’s Chinatown, but then she took a decidedly different path for a young Chinese woman in the early 1900s. Ted wanted to write about his grandmother’s journey, and his family’s tangled history. He originally wrote a piece for the Angel Island Immigration Station’s “Immigrant Voices” project, and our article here is an adaptation of Ted’s original piece.

“I grew up in a neighborhood between San Francisco’s Chinatown and Nob Hill,” says Ted, noting that it was “not unlike growing up being both Chinese and American. I am blessed that I knew my grandmother, who wouldn’t speak to me in the morning unless I first said ‘Jo san, Ah Mah,’ [‘Good morning, Grandmother.’]. Then I’d run off and watch the Saturday Westerns on TV!”

Here is her story, as told by Ted:

I stand in the graveyard of Ruby Hill, a lonely, windswept ghost town in central Nevada. Miles of empty desert, snowy mountains, fields of ripe produce, and a hundred little towns lie between me and San Francisco. Yet, there is an eternal, immutable bond of family that crosses these miles and ties desolate Ruby Hill to the historic immigration station at Angel Island in the middle of San Francisco Bay.

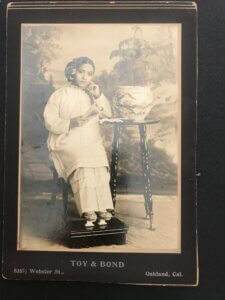

My paternal grandmother, Tye Leung, was born in Chinatown in 1887. When she was just 12 years old, she ran away to Chinatown’s Presbyterian Mission Home rather than be sent to Montana to enter into an arranged marriage. At the mission home, under the tutelage of Donaldina Cameron, Tye learned English and became a Christian woman. She started serving as an interpreter for Miss Cameron, and assisted many police raids of Chinatown brothels to rescue young women from prostitution.

In 1911, because of her dedicated compassion and English language skills, Tye accepted a position to become an interpreter and “assistant matron” at the new immigration station at Angel Island. Her new job made her the very first Chinese-American woman to become a U.S. civil servant. And, in 1912, she was one of the first—and quite possibly the very first—Chinese American to vote in an presidential election.

It was at Angel Island, roughly a year later, that she met Charles Schulze, a burly Austrian who worked as an Immigration Service inspector. They fell in love and wanted to marry. Due to California’s anti-miscegenation laws (prohibiting relationships between white people and those of other races), they had to travel to the state of Washington to get married. A year later, bowing to deep-seated prejudice against interracial marriage, they both resigned from the Immigration Service.

Who was Charles Schulze? Why did he buck conventional practice, fall in love with and even dare to marry a Chinese woman? Maybe it all stemmed from his immigrant father, Carl Schulze, my great-grandfather. Like many others in Europe at that time, Carl sought a new life in America. He emigrated from Prussia in the 1860s, ending up in Illinois. After becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1864, he made his way to Santa Cruz, California, with his new wife, Irene.

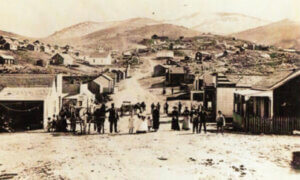

In the 1870s, gold and silver mining was still producing millions of dollars in Nevada, so Carl, now Anglicizing his name to Charles, set off to make his fortune. Due to the rough life in mining towns, Charles had to leave Irene and his new infant back in Santa Cruz. Charles eventually found gainful employment as the appointed U.S. postmaster for the booming town of Ruby Hill, in the middle of the desert, over 200 miles east of Reno.

During this time, back in Santa Cruz, illness took the life of his first child and almost claimed his wife as well. Perhaps this stirred a higher calling in him, because he came back to study medicine at the University of the Pacific in Oakland, graduating in 1877 with a medical degree. Happily, this was celebrated by the birth of his second child, also named Charles, in Santa Cruz.

Now officially “Dr. Charles Schulze,” he again took the long, arduous journey alone by train and stagecoach back to Ruby Hill, where he became the town doctor as well as regaining his position as postmaster. Tragically, the strain of study and travel became too much and at the young age of 38, my great-grandfather Charles died suddenly of a stroke. He was buried in the Masonic cemetery in nearby Eureka in February, 1878, never again to rejoin his wife and child.

Young Charles lived quite an exciting life in Santa Cruz. After a short enlistment in the California Naval Militia during the 1898 Spanish American War, he worked as a conductor on the Santa Cruz Electric Railway. Upon moving to San Francisco with his mother in 1901, he became a motorman on the Sutro and Market Street Railway. Looking for something a bit more fulfilling, Charles took a job as a private patrolman for the famed Morse Detective Agency, with Chinatown as his beat. In 1905, he secured a position as an inspector for the U.S. Immigration Service. He was initially assigned to the old and decrepit shed at Meigg’s Wharf, a 200-foot-long wharf that once jutted into the bay at the base of Telegraph Hill. After five years at the wharf location, he was reassigned to the newly built immigration station on Angel Island.

In 1912, at the immigration detention center, against the backdrop of a multitude of immigrant hopes, dreams, disappointments, and tragedies, Charles and Tye, two unlikely but kindred spirits met and fell in love. Despite having to fight prejudicial attitudes that hounded them for the rest of their marriage, they went on to have four successful and loving children. Charles passed away in 1934, and Tye lived on until 1972.

My grandmother lived a quiet life, never officially receiving any recognition for her historic accomplishments. She never sought fame or fortune, yet even in retirement after World War II, she still helped many Chinese war brides become American citizens.

And so I stand today in the Nevada desert, the fourth-generation son, in a small quiet graveyard just below the desolate ruins of Ruby Hill. I stretch out my hands to touch generations, hundreds of miles and over a hundred years apart. I kneel down to touch the soil of the little graveyard with one hand, where my great-grandfather Dr. Carl Schulze has lain in an unmarked grave for 136 years. I reach out with my other hand to the shores of Angel Island where Carl’s son Charles walked with beautiful Tye Leung, perhaps hand-in-hand, always in secret. Finally, generations unite in spirit, my family’s Angel Island story has at last come full circle.—Ted Schulze/FOCC volunteer

Tye Leung Schulze’s story by her grandson Ted Schulze is adapted from an original article for the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, and is reprinted with the foundation’s permission. Visit the AIISF website for more immigrant stories and information.

More on Tye Leung Schulze

VIDEO: PBS “Unladylike” series: Tye Leung Schulze

ARTICLE: National Park Service “Persons” profile: Tye Leung Schulze

ARTICLE: State of Oregon Women in Suffrage profile: Tyel Leung Schulze