Family Ties

A self-taught genealogist and Quan descendent sheds light on her family’s legacy.

On the surface, Carly Morgan doesn’t strike you as someone with links to China Camp, or reasons to be interested in its history. After all, she’s a former attorney, born in Southern California and now living in Salt Lake City with her husband, Kyle, and their three kids, ages 6 to 12. How could she be connected to our 1,600-acre park on the edge of San Francisco Bay?

Quite simply, Carly is a Quan. Carla’s grandmother, Bertha Quan, was born and raised at China Camp along with her brothers and sisters, including Frank, the final member of the Quan family to live at China Camp. (Frank lived in his cabin at China Camp Village until his death in 2016.) Carly’s “Auntie Gette” is Georgette Quan Dahlka, the last Quan to still work at the park, volunteering in the cafe on most weekends.

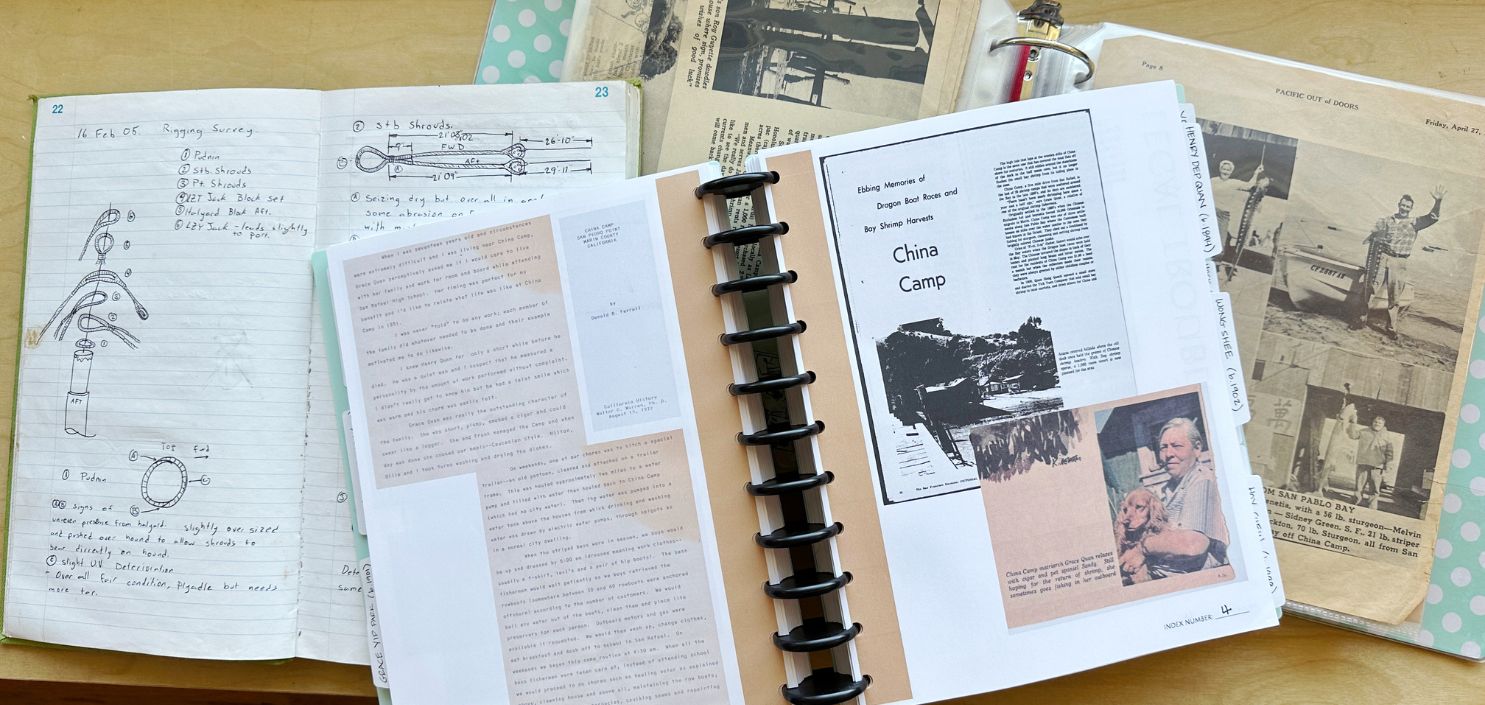

Another thing about Carly: she’s a self-taught genealogist who ditched law in favor of starting her own business, called Family Tree Notebooks. Over the years, she acquired a treasure trove of boxes filled with clippings, letters, and photographs about China Camp and the Quans. As a side hobby, Carly started organizing all those inherited boxes, making the connections, filling in the blanks, and helping to preserve the Quan legacy. Here, Carly shares her inspiration, her process, what she has learned about her ancestors and China Camp, and why it matters.

Why is it important to preserve the Quan legacy and the stories of China Camp?

My family is lucky to have a deep, rich history. I wanted to understand it better. My great-grandma, Grace Quan, had a fascinating, bizarre, confusing version of our family’s history, so I started researching it while I was in law school. It was a side project. Over time, I realized I wanted to support myself more as a writer and storyteller than a lawyer. I started my business, Family Tree Notebooks, four years ago, and I’m lucky to have found a passion that supports me and that I love.

What were your challenges in starting to make some sense of all the material you had inherited?

The Quans didn’t fit into a typical family tree with nice ivy-trimmed pages, with two parents with jobs, a home, two kids, and a dog. We were a strange kind of eclectic Chinese family, with ancestors who came to the U.S. from different places and in different ways. They weren’t allowed to be landowners. They couldn’t vote. They had to carve out their own lives but weren’t recognized as citizens. It changes how you do the genealogy. I had so many notes and photographs and pieces. I needed to lay it all out, organize it, take it back to my family and tell them this is who we are and this is what we need to remember.

How did you start building the story?

My family history didn’t fit into traditional family trees or scrapbooks—there was racial diversity. There were gay people. There were people who didn’t have a place. It was heart-breaking. There was nowhere to put them. So I created my own pages, which were the beginning of my company. There are a lot of people out there like me, with families that don’t fit the traditional mold. I think it’s important to tell the story that feels like your family, not just names you put into someone else’s ideal or project.

When you started to tackle the Quan family history, did you uncover any surprising treasures?

Under the circumstances, the Quan family thrived, but in truth they weren’t really doing well—they were just getting by. There was no sense of precious things—collectibles and the like. I kept thinking I might find some cool piece of jade hidden in a box, but there was nothing. Great-Grandma Grace wasn’t a precious woman, and her home wasn’t filled with antiques. So what we have are photos, news articles, and home movies, but no stuff. It just wasn’t there.

What Quan stories stand out to you?

The story of my great-great-grandmother, Yee See Quan. The differences in the struggles of her day-to-day life and mine—how she lived—seem almost alien to my life.

We’d have nothing common to talk about. I have a bubble portrait of her, likely taken around 1900. To look at it you’d probably just see her as a pretty woman. It’s flat. But her life—growing up in China and coming to San Francisco—is richer than anything I will ever know. In doing research, it’s a privilege for me to get to know her, who she was, and to see her as more than just a pretty picture. She was the matriarch who sparked the whole family.

What made her story stand out to you?

She probably came on a ship, as cargo, around the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act. [Passed in 1882, the law enacted a 10-year ban on Chinese laborers coming to the U.S.] The ban made it extremely difficult for men already in San Francisco to find a Chinese woman to marry. People behind the law probably hoped it would make Chinese men go back to China to find wives.

At around the same time, there was a depression in China. Young daughters weren’t allowed to work; they just consumed. So their parents sold them as cargo on ships bound for San Francisco. They’d deboard in broad daylight, and were put into auctions to be sold as prostitutes, some to be chained to beds in basements. The police would be there at the docks, not to protect the women from this fate, but to keep them from trying to run to escape, or from jumping off the piers to drown themselves.

What happened to your great-great-grandmother when she got to San Francisco?

At the auctions, men who had the means could buy women for wives. That’s probably how she met and married Quan Hung Quock, my great-great-grandfather. He was already a merchant, which allowed him to go back and forth to China. He was exactly the kind of person who would buy a wife. He probably paid for her, then paid to get the bubble portrait of her. So she was his possession. Even so, she did get to marry a man who prized her, and they did have two sons. And she was devoted to her husband her whole life. After he died and she had to raise her children alone, she burned money for him so he would have food in his afterlife.

How do you think of her now that you know her story?

Yee See Quan was this tiny little thing who ran the bait shop, who raised her family after her husband died. She wasn’t a larger-than-life character like Grace Quan. She was more of a hidden person. But she was actually the person who kept everyone going, who kept the family together.

What holes do you still have in the story of your family and China Camp?

Research wise, there is more to find out about the community that was there, early on. Up until the early 1900s, the U.S. census just identified people as “Chinamen,” not individuals with names. I’d love to create a more concrete picture of that time.

We imagine the thriving China Camp community in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, because the people all had names, and they weren’t all Chinese. (Great-grandmother Grace was Caucasian, though she was raised in a Chinese orphanage.) But before that time, there was a whole community that was pushed out, and I feel passionate that we don’t let their stories disappear into the ether. There are letters and other things; now it’s a case of connecting the dots.

How have you personally kept traditional Chinese culture alive in your own life?

One way has been with my children. In Chinese culture, when a baby is born, elders give the child his or her Chinese name. It’s not a name that is normally used, but it’s a tradition, with the name revealed in a celebration calledl a red egg party. In 2013, my middle son had his red egg party at China Camp. My grandmother Bertha—my mom’s mom—gave my son his Chinese name.

What do your kids think of your genealogy work, and their Chinese history?

My 12-year-old is disinterested in everything I do right now. But she and my other kids were very close to my mom, and devoted to the stories she shared with them. They have a warm spot for China Camp.

—by Harriot Manley/FOCC volunteer