Tiny shrimp, big challenges

The staggering obstacles facing shrimp-fishing villages

Discrimination and prejudice, hostile officials, dangerous work and living conditions—life wasn’t easy for the Chinese immigrants who settled in the shrimping villages that circled San Francisco Bay in the late 1800s. Here, local historian Chris Carlson (who gives a hat-tip to colleague David Gallagher), in an article first published on FoundSF.org, chronicles the growth of these camps, and the challenges faced by the people who lived and worked there.

A community of Chinese shrimp fishermen made their home along the shores of India Basin, on the north shore of San Francisco’s Hunters Point, until 1939, when the U.S. Navy took over the land under eminent domain for the [future] Naval Shipyard. The Health Department came in and burned the shacks and docks that once provided a small village of fishermen and their families a steady living in the abundant shrimp harvest from San Francisco Bay.

But that was not the first time the Health Department had come in and destroyed the livelihood of Hunters Point shrimpers. The “Butchers’ Reservation” was established [by non-Chinese] in the Islais Creek marshes [northwest of Hunter’s Point] in the 1870s; by the 1890s new public health concerns with microscopic threats to public hygiene led to allegations that “Butchertown shrimp” were contaminated with ptomaine—a bacteria-produced protein laden in the tons of waste emanating from the slaughterhouses every day.

But that was not the first time the Health Department had come in and destroyed the livelihood of Hunters Point shrimpers. The “Butchers’ Reservation” was established [by non-Chinese] in the Islais Creek marshes [northwest of Hunter’s Point] in the 1870s; by the 1890s new public health concerns with microscopic threats to public hygiene led to allegations that “Butchertown shrimp” were contaminated with ptomaine—a bacteria-produced protein laden in the tons of waste emanating from the slaughterhouses every day.

In 1899, the city’s health officer, accompanied by the city’s chemist and police officers and a small brigade of Health Department inspectors, invaded the Chinese encampment along the slopes of Hunter’s Point and condemned and set fire to 15,000 pounds of shrimp. (Months later, the city’s Board of Health admitted . . . that the shrimp were not “germ-ridden” after all.)

From the beginnings of San Francisco’s urban growth, Chinese immigrants established fishing villages around the bay. The southern shores of San Francisco at Hunters Point were one, but there were others too, especially at China Camp (Point San Pedro) in Marin County and directly east across the Bay at Point Pinole near Richmond.

The Chinese fishermen sailed their redwood fishing [junks] to the mudflats. They dropped sail and set the large, triangular nets by staking them into the mud in long lines. The mouths of the nets were set open to the oncoming tide to catch shrimp swept along by the current. As the tide slackened, the fishermen raised nets and dumped the live shrimp into large baskets that were then stored in the boat’s hold. The nets were reset in the opposite direction for the next tidal cycle. After two tidal cycles, or about 12 hours, the holds were full and the fishermen returned to camp to process the catch.

Along the shores of Hunters Point, Chinese shrimpers lived and worked one of the most fertile shrimping beds in the San Francisco Bay. Chinese San Franciscans had dominated the shrimping industry in the region since the 1870s. By 1895, the 5.4 million pounds of shrimp harvested in the Bay Area—almost entirely by Chinese fishermen—was second only to the Bay Area oyster industry in market value and tonnage.

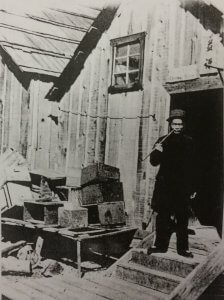

[According to historian Andrew Robichaud’s book, Animal City: The Domestication of America (Harvard University Press; 2019), the “Chinese ‘shrimp camps’ that appeared in the 1870s were more than just work environments. Shrimp farmers often lived alongside the shores where they worked—sometimes in the very same structures. In some ways, the spatial isolation of these camps probably offered refuge for Chinese men, away from a discriminatory landscape downtown.

To outsiders, however, the lives and work environments of Chinese shrimpers were improper. Not only did Chinese men live in the same places they worked in substandard conditions, but—even more shocking to white observers—Chinese men used their bare feet and wooden shoes to separate meat from the shells. Adding to white hostility, most of the shrimp were exported to China, where their meat was sold as inexpensive food and the [shrimp shells pulverized for fertilizer.] This export economy angered many whites, who saw the natural bounty of the bay sold away to China for the profit of the Chinese immigrants and merchants. To white observers, the whole operation was backwards.”

—by Chris Carlson and David Gallagher

This article is reprinted by permission from FoundSF, a “participatory website inviting historians, writers, activists, and curious San Francisco citizens to share their unique stories, images, and videos from past and present.”