Scientists get crabby—and muddy—at China Camp

Efforts focus on curbing the spread of the invasive and destructive green crab.

Renowned for its beauty, and a hub of marine activity, San Francisco Bay is also one of the most invaded estuaries in the world. Tankers, freighters, and other ships constantly bring people and goods to our region—and can unwittingly bring invasive species too. Microscopic larvae and other small creatures can hitch a ride to a new destination by latching onto a ship’s hull (think barnacles) or by surviving in the boat’s ballast water.

While some of these non-native species do not survive or thrive in the Bay Area once they get here, some do. Non-native species that become established and cause damage to human health, the economy, or to native plants and animals through competition or other reasons are considered invasive.

Unfortunately, China Camp State Park is now home to several invasive species, including the green crab, Carcinus maenas, a native of Europe. Green crabs are voracious predators and can deplete native populations of clams and small creatures called amphipods, both of which are important food sources for China Camp’s native and migratory shorebirds. Green crabs also compete for space and food with San Francisco Bay’s native crab species, including our commercially important Dungeness crab (Cancer magister). Adult green crabs also consume juvenile native crabs, putting even more pressure on the bay’s native crab populations.

Invasive green crabs may also harm native plants and cause expansive die-offs of eel grass. At China Camp, scientists are conducting experiments to learn more about the potential impacts of green crabs on China Camp’s critically important salt marsh plant. Work includes placing circular crab traps in habitat fronting the park’s Ranger Station. (You can see them from our Bullhead Flats day-use area.) This collaboration between UC Davis and San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (SF Bay NERR), following State Park regulations, will help us understand how the park’s salt marsh plants will respond to invasive green crabs and other stressors, such as increased flooding from storms and sea-level rise caused by climate change.

Results will help coastal resource managers better understand the individual and combined impacts of these stressors, so managers can prioritize and address each issue in long-range conservation planning.

How crab fishermen can help

If you’re using a crab trap in San Francisco Bay, or you know someone who crab-fishes here, you can help reduce the threat of this invasive species. (Note: It’s against state law to disturb or trap any type of animal—including crabs—at China Camp.)

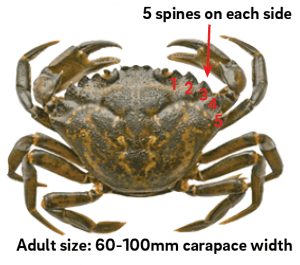

The first step is to learn how to identify green crabs. Shell color ranges from green to brownish-red in color, with the carapace measuring 60 to 100 millimeters (roughly 2.5 to 4 inches) wide.

Next, count the jagged spines on either side of the crab’s eyes. While the Bay Area’s native species have either three or ten spines on each side (depending on the species), green crabs have five spines. (See image at left.) If you’ve captured a green crab, you should remove it from the bay and destroy it.

To learn more about efforts to understand and control invasive species in San Francisco Bay, go here. The Stinson Beach community is also taking steps to control green crabs. Visit this website for details.—by Julie Gonzalez, SF Bay NERR.

Julie is a doctoral candidate at UC Davis, and a Margaret A. Davidson fellow with SF Bay NERR, a longtime partner with Friends of China Camp and China Camp State Park. Julie is interested in how coastal estuarine systems will respond to climate change stressors including sea-level rise, and how we can use this knowledge to improve habitat restoration efforts. Learn more about Julie’s research here.